Things to know before you begin...

The consolidation timeline is easier to understand if you know the municipalities that existed before the boroughs replaced them. See below for a borough by borough explanation.

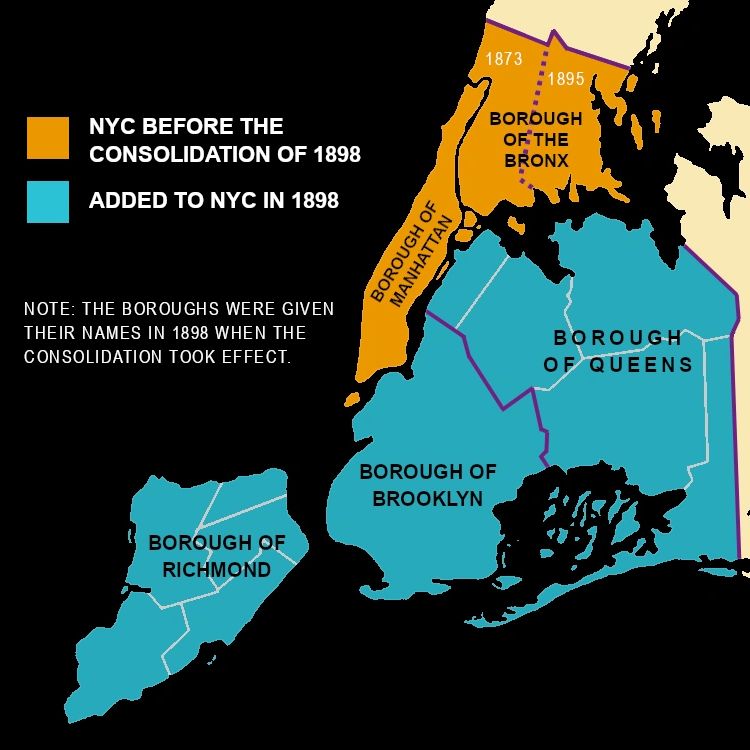

Understanding The Consolidation Map

Manhattan — This one is easy. All of Manhattan was already part of New York City.

The Bronx — The territory of today’s Bronx Borough was annexed by New York City in two stages before the consolidation of 1898. It originally consisted of a handful of towns in Lower Westchester County. The towns west of the Bronx River were annexed in 1873; the towns east of the river were annexed in 1895. This non-Manhattan piece of New York City was called The Annexed District until it was renamed The Bronx with the consolidation.

Brooklyn — The territory of today’s Brooklyn Borough was originally occupied by six different towns, one of which was named Brooklyn. The Town of Brooklyn kept growing throughout the 1800s, eventually becoming a city and annexing, one by one, all the other towns. By 1896 the City of Brooklyn filled the entire area of the original six towns.

Staten Island — At the time of the consolidation Staten Island was a collection of separate towns. Taken together they were called Richmond — the island’s county name to this day. In fact, the original borough name was Richmond, too. But that was officially changed to the commonly used Staten Island in the 1970s.

Queens — At the time of the consolidation the territory of today’s Queens Borough consisted of Long Island City — yes, it was a city — and a patchwork of towns and parts of towns. (Helpful Note: Many people who begin to study the consolidation are confused by the fact that when Queens Borough was created in 1898 it was not coextensive with Queens County. Nassau County did not exist, so Queens County extended from the East River to the Suffolk County line! Read that again, so you understand it. So, Queens Borough occupied approximately one-third of Queens County. This madness ended in 1899 when Nassau County was created and the diminished Queens County was made coextensive with Queens Borough. However, the Queens Borough line was altered slightly in the process, and, as a consequence, New York City lost about 12 square miles of territory.)

A Word About Population

The cities of New York and Brooklyn dominate the consolidation story. In the 1890s New York City was the most populous city in the country and Brooklyn was the third or fourth most populous. It is difficult for modern-day New Yorkers to appreciate just how empty Queens, The Bronx, and Staten Island were by comparison. Here are the population figures at the time of the consolidation:

- Manhattan - 1,960,000 (56%)

- Brooklyn - 1,180,000 (34%)

- The Bronx - 150,000 (4%)

- Queens - 140,000 (4%)

- Staten Island - 70,000 (2%)

Image: The Consolidation of Greater New York Statue by Albert Weinert is located inside the Surrogate's Court Building in Manhattan. It depicts an allegorical City of New York on the left, City of Brooklyn on the right, and the young new consolidated city in the center. The other municipalities that joined Greater New York are ignored, although the five borough names are included at the sides, under the eagles.

The CONSOLIDATION TIMELINE

1857 • Andrew H. Green and the Central Park Commission

After land was purchased and cleared by the City of New York, the New York State legislature created a commission to design and build Central Park. Andrew H. Green was one of eleven commissioners appointed to this new Central Park Commission. In short order Green became its leader and spokesman.

Image: Green, left, atop the Willowdell Arch in Central Park, 1862. Next to him is the the creative team that worked under the Central Park Commission, including Frederick Law Olmsted, right, and Calvert Vaux, left of center.

1865 • Green Plans Manhattan

The legislature gave the Central Park Commission more and more city planning authority in Manhattan. Under Green’s leadership the commission planned streets, parks, cultural institutions, and other public improvements around Central Park, above 155th Street, and on the Upper West Side.

1868 • Green: Consolidation Would Cure Bad Planning

The legislature authorized Green to recommend public improvements across the Harlem River — in what was then Lower Westchester County — so that the territory on both sides of the river might be developed in a coordinated and rational way. In a written report Green expressed intense frustration over the piecemeal, shortsighted, and uncoordinated planning efforts he found in the Lower Westchester towns. He suggested a cure for the problem, which he projected across the entire metropolitan region: “Bringing the City of New York and Kings County, a part of Westchester County, and a part of Queens and Richmond, including the various suburbs of the city, within a certain radial distance from the center, under one common municipal government.” Although Green’s grand scheme was largely ignored and the Central Park Commission was dissolved in 1870, this proposal, buried deep inside an obscure report, would provide the basis for the consolidation of 1898.

Image: Andrew H. Green, c. 1870

1873 • NYC's First Expansion Beyond Manhattan

The Lower Westchester towns of Kingsbridge, West Farms, and Morrisania were annexed to New York City. This is the western portion of today’s Bronx.

1883 • The Great Bridge

After fourteen years of construction, the Brooklyn Bridge opened. Many people predicted that the physical union of New York and Brooklyn would make the political union of the two cities inevitable.

Image: The caption of this illustration which was published when the Brooklyn Bridge opened is "A union of hearts and a union of hands."

1888 • The Business Community Revives Consolidation

In its annual report the pro-business Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York published an essay titled "The Imperial Destiny of New York" that endorsed consolidation. Soon after, The Real Estate Record and Builder's Guide weighed in: "We believe that every interest of the populations involved would be benefited by organizing this metropolitan district under one government ... Their interests are interrelated. The present separation is unnatural and leads to waste and misgovernment." The Guide also mentioned that Baltimore, Chicago, Philadelphia and Boston were growing through annexation.

Image: Merchants complained that New York Harbor — the economic engine of the region — was mismanaged and polluted by all the separate municipalities that touched its waters.

1889 • Andrew H. Green is Back

Andrew H. Green stepped back onto the scene. At his urging the New York State legislature created a Greater New York Commission to explore the consolidation question.

1890 • Greater New York Commission

Green was made president of the commission, and J.S.T. Stranahan, a prominent Brooklyn civic leader, was made vice president. Public hearings were held and maps were drawn.

1891 • Green's Consolidation Bill Dies

With the approval of his fellow commissioners, Green sent a Consolidation Bill to the legislature. It included municipal boundaries as well as a description of the new city's administration and charter. The bill died, presumably because it was too inclusive.

1892 - 1894 • The (Non-Binding) Referendum

Green and his allies changed tactics — they pushed for a referendum. It would take three attempts but the legislature finally passed a Referendum Bill in 1894. To show support for the various referendum bills, pro-consolidation Brooklynites formed the Consolidation League. The referendum was scheduled for the November elections. It would be non-binding.

Image: One of many pamphlets published by the pro-consolidation lobby

1894 • The Pro-Consolidation Arguments

The pro-consolidation camp distributed leaflets, gave speeches, and sought allies among good-government organizations and newspapers. Some of their arguments were as follows:

- New Yorkers were told that their city needed to expand if it were to achieve its "manifest destiny" as the premier metropolis in the country. A fast-growing Chicago, they were reminded, was nipping at their heels.

- Merchants and bankers were told of the economic benefits and efficiencies that would come with comprehensive city planning and a unified, well-administered harbor.

- Brooklyn real estate interests were told that the influx of New York City tax revenue that would come with consolidation would reduce taxes, pay for badly needed civic improvements (water supply, bridges, sewers, etc.), and provide debt relief. Brooklyn, it should be noted, was nearly bankrupt and had a failing water supply.

- Good government advocates were promised the opportunity to root out political corruption and abuses when a new city government was designed.

- And the voters at large were assured that an expanded city with cheaper housing outside of Manhattan would help reduce "poverty, disease, crime, and mortality" by relieving crowding in the slums.

Image: Pro-consolidationists argued that if Father Knickerbocker and Miss Brooklyn joined forces they would leave Mr. Chicago in the dust.

1894 • The Referendum Results

On the whole, consolidation passed. Voters in Manhattan came out heavily in favor of the measure. But the highest pro-consolidation vote, by proportion, came from Staten Islanders; they voted approximately 4-to-1 in favor. This is not altogether surprising. Many voters in the distant districts of the metropolitan region were eager to tap into the big city revenue that consolidation would bring them. The results in Brooklyn were stunningly close: 64,744 votes in favor, and 64,467 opposed — a difference of only 277 votes out of over 129,000 votes cast!

1894 - 1895 • The Anti-Consolidationists Rally

Buoyed by the positive referendum results, Andrew H. Green and his allies began drafting a bill to make consolidation a reality. But the returns also shocked Brooklyn's anti-consolidationists into action. Since the vote was non-binding, they knew that all hope was not lost. They were led by the city's leading newspaper, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and the newly formed Brooklyn League of Loyal Citizens. The League was organized by old guard Protestant cultural and religious leaders. They pressed for what they called "resubmission" — a second, binding referendum. Their anti-consolidation case was as follows:

- Consolidation would not lower Brooklyn's taxes because New York City was already committed to a number of costly projects which, when added to Brooklyn's needs, would boost the current rates.

- Union with New York would overrun Brooklyn with slums filled with alien, impoverished, and criminal newcomers.

- It would also infect Brooklyn's politics with Tammany Hall crooks.

- Meddling by non-Brooklynites would ruin the city's well-respected school system.

The Eagle and Loyal League mocked the consolidation movement as "Green's hobby." They generated editorials, cartoons, speeches, and pamphlets to present their arguments to the public. The Eagle even sponsored anti-consolidation essay and song contests. The winning song was titled "Up with the Flag of Brooklyn."

Image: Prospect Park after consolidation, as imagined by The Eagle: Miss Brooklyn weeps near a statue of Boss Tweed while an innocent citizen is beaten by a policeman

Up with the Flag of Brooklyn by John Hyatt Brewer

1895 • Stalemate, then Enter the "Easy Boss"

Because many Brooklynites did not identify with the elite Protestant ideals put forth by the Loyal League, the League never developed a wide or diverse base. Nonetheless, the opponents of consolidation were able to muster enough political resistance to effectively kill two consolidation bills, one proposed by Andrew H. Green and another by the governor of the state, Levi P. Morton. When the legislative session ended in May, the consolidation question had reached a stalemate.

A separate, smaller, and much less controversial annexation measure was signed into law in June. The eastern portion of Lower Westchester County was made part of New York City. The city already owned extensive parkland in this district, so the move was unsurprising. This area, taken together with the western section that had been added in 1873, was called The Annexed District — today's Bronx.

The most powerful political player in New York State in the mid-1890s was Thomas C. Platt, the head of the state's Republican Party. Governor Morton, the majorities of both houses of the legislature, and the mayors of most large cities in the state — including New York City and Brooklyn — were Republicans. They all answered, to some degree, to Platt.

Platt, though famously soft-spoken and courteous, was a ruthless champion of his party. His nickname was the Easy Boss. He had been ambivalent about consolidation, but in the fall of 1895 he decided that the measure would benefit the Republicans, so he resolved to push through a consolidation bill the following year.

Platt's involvement in the consolidation movement would sour the enthusiasm of some of the early supporters of the idea, especially good-government types and some business leaders. He was too politically partisan, they feared, to be trusted with determining the destiny of the new mega-city.

Image: Thomas C. Platt with the legislature in his pockets and the governor under his arm

1896 • Platt's Plan

Platt chose a loyal lieutenant, state senator Clarence Lexow, to execute his plan. After a series of public hearings in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Albany, Lexow's joint sub-committee submitted a consolidation bill to the legislature. The bill defined the boundaries of the greater city as Andrew H. Green had originally proposed them. It specified that a charter for the new city would be written and approved after the bill was passed but before January 1, 1898, when consolidation would take effect. There would be no resubmission.

The Lexow Bill was passed by both houses of the legislature, but then, as required by law, it was sent to the mayors of New York, Brooklyn, and Long Island City for their approvals. The mayors of New York and Brooklyn vetoed the bill. The legislature would have to repass the bill to override the vetoes.

Image: Clarence Lexow's subcommittee holds a public hearing in Brooklyn

1896 • The Bill Passes at Last

The Senate repassed the Lexow Bill over the mayors' vetoes. Next, it headed to the Assembly. There the anti-consolidationists would mount a valiant last stand. The Brooklyn League of Loyal Citizens and Manhattan opponents persuaded a large bloc of Brooklyn Republicans and several upstaters to vote no, whereupon about twenty Tammany Democrats withdrew their support and also voted no.

This unexpected setback sent Platt scrambling to rally his forces with promises and threats. He gathered votes from a few Green-loyal Upper Manhattan Democrats, three Brooklyn Republicans, and his faithful upstate Republican base. In the end, the Assembly passed the Consolidation Bill with only two votes to spare! "Nothing Mr. Platt ever undertook cost more effort or gave him more anxiety than this legislation," wrote one of his political colleagues.

On May 11th Governor Morton signed the bill into law.

Image: Boss Platt stuck in his thumb and pulled out a plum: Greater New York!

1896 - 1897 • The Greater New York Charter

A commission of nine members drafted a charter spelling out the the structure of the government that would run Greater New York. Andrew H. Green was a commissioner but he was too ill to fully participate in the work.

One controversial aspect of the charter was the invention of the "borough system," whereby the greater city would be divided into smaller districts. Green and others argued that they had just fought a decade-long battle to unite the city, so why would the commission want to divide it up again? Their opponents said that, at 300 square miles in size, the new metropolis was too big to govern well from City Hall. Boroughs would give residents in the far-flung reaches of the city more local control. The local-control advocates proposed that there be nine boroughs. The two camps, of course, compromised at five.

Despite the commission's best intentions, the hastily-written final document was deeply flawed. Brooklyn's interests, however, were favorably represented in the new charter. Thanks to Platt's influence, the charter passed the legislature and was signed by the new Republican governor, Frank Black, who gave his pen to Platt as a keepsake.

Image: The proposed nine-borough Greater New York

1898 • Consolidation Day: a New City, a New Mayor

On New Year's Eve of 1897, despite gloomy, wet weather, a crowd of 50,000 festive people — marching in bands, riding on floats, and shooting off fireworks — strode down Broadway to City Hall Park. At midnight (or thereabouts) the mayor of San Francisco raised the flag over City Hall using a mechanism activated by a long-distance electrical signal. Church bells rang and steam whistles tooted. ln Brooklyn's now-Borough Hall there was a grudging ceremony that many described as a funeral.

The next day, Robert Van Wyck, an unremarkable Tammany Democrat, took office as the first mayor of the consolidated city. Platt's dream of a Republican-led greater city had been doomed when a reform Republican, Seth Low, entered the recent mayoral race and split the G.O.P. vote with Platt's man, Benjamin F. Tracy.

Image: A sad night in Brooklyn, December 31, 1897

1899 • Nassau County Takes a Bite Out of the City

As mentioned earlier, when Queens Borough was created it was not coextensive with Queens County. Queens County extended from the East River to the Suffolk County line. In 1899 Nassau County was created and the diminished Queens County was made coextensive with Queens Borough. But the Queens Borough line was altered slightly in the process, and, as a consequence, New York City lost about 12 square miles of territory.

1903 • Andrew H. Green's Tragic End

Immediately following the consolidation Andrew H. Green was universally hailed as "The Father of Greater New York." He was presented with a gold Greater New York Medal as a token of gratitude.

Green's life came to a shocking end on November 13, 1903 when, at the age of 83, he was shot to death outside his home by a deranged and paranoid gunman named Cornelius Williams. It was a case of mistaken identity. Williams mistook Green for another elderly man who he thought was spreading malicious rumors about him.

A large oil painting of Green was hung in City Hall, but nothing came of the many proposals to honor him with a grand monument.

Image: Andrew H. Green's murder scene as depicted in a newspaper

1923 & 1948 • Silver and Golden Jubilees

The City of New York marked the 25th and 50th anniversaries of the consolidation with parades and civic expositions at the Grand Central Palace.

The 1948 Golden Jubilee was particularly extravagant, and featured an additional spectacle: an airshow at the city's brand new New York International Airport (later renamed J.F.K. Airport). The U.S. Post Office even issued a five-cent airmail postage stamp featuring the Golden Jubilee logo to mark the occasion.

Image: The 1948 Golden Jubilee airmail stamp

1929 • "Five Symbolical Trees"

Andrew H. Green was finally given an official monument in the city he worked so hard improve when a stone memorial bench was installed on a hilltop in northern Central Park. The inscription on the bench described Green as "the directing genius of Central Park" and "The Father of Greater New York." The bench was placed at the site where "five symbolical trees" — representing the boroughs, of course — had been planted the year before.

Image: The Green Memorial Bench on the day it was dedicated. The seated men included a Green family member, a Parks Department official, and colleagues who knew Andrew H. Green when he was alive.

A Word of Aknowledgement

The information and images on this page were assembled from many sources, but the writings of one particular historian, David C. Hammack, deserve a special mention. Dr. Hammack's research on the consolidation is unmatched, and anyone interested in the topic should read his book Power and Society: Greater New York at the Turn of the Century.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.